Oct. 9, 2019

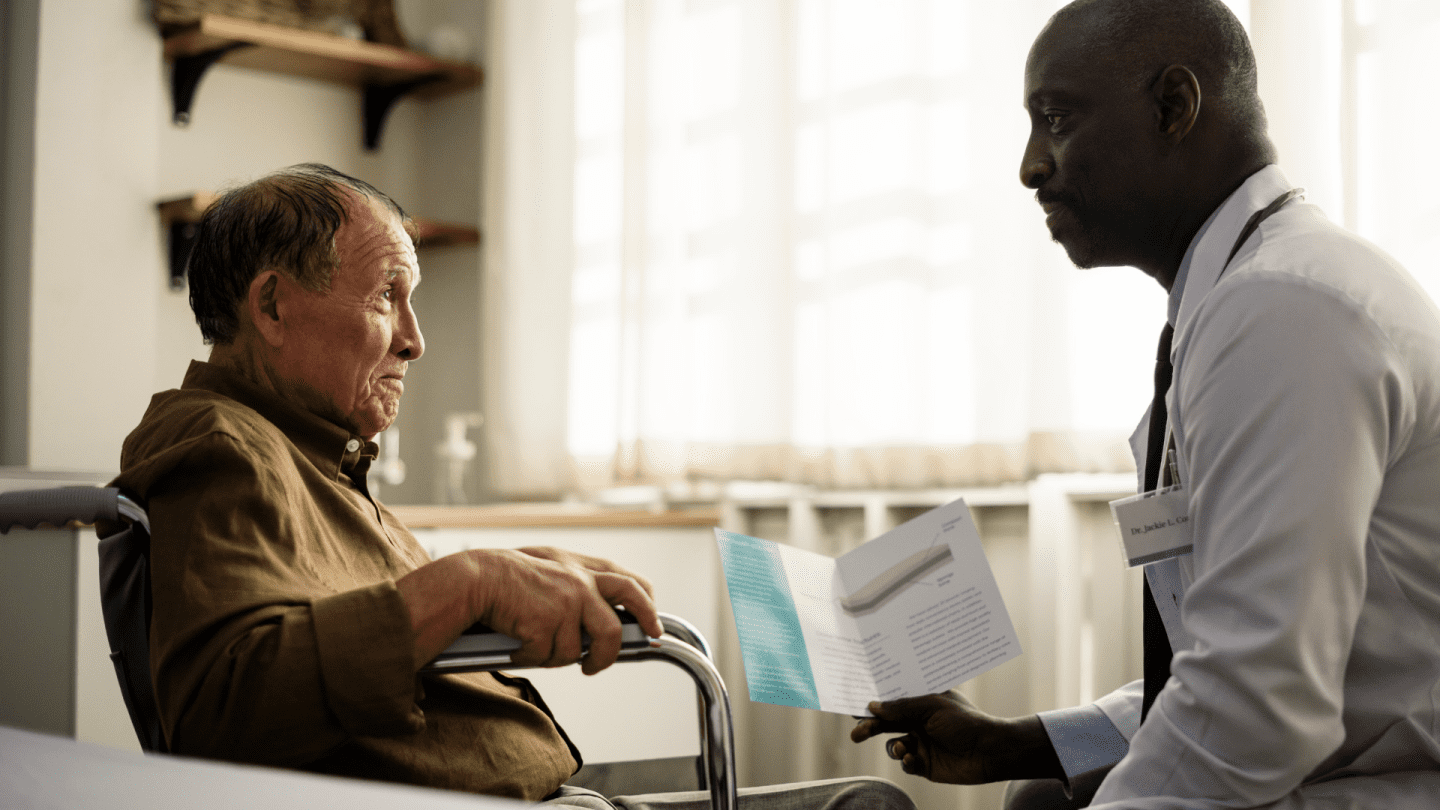

Serious illness affects more than a person’s health. A life-limiting diagnosis can have profound effects on a patient’s own identity. It can conscript the patient’s loved ones into burdensome caregiving. It can start a pinball’s journey through doctors’ offices and hospitals and home health agencies, careening from provider to provider. This all too frequently happens without an intentional pause to consider a question fundamental to human dignity: What does this patient truly want right now?

A number of Bay Area doctors have become eloquent, visible leaders in centering this question, including Jessica Zitter, BJ Miller, Shoshana Ungerleider, Lucy Kalanithi, and Steve Pantilat. 1 They and others have documented ways that American health care may be able to offer an extra layer of support to improve the quality of life of patients and families burdened with a serious diagnosis. One way is to employ a broader team of nurses, faith leaders, and social workers that can help patients and families work through these inevitable, painful discussions about their values and wishes for care.

We hope, amid all that heaviness, to provide relief from the symptoms and stress of a serious illness regardless of whether the patient is at an early stage of their illness or facing the end of their life. The vision to improve care for these patients came from our donor and board chair Joyce Stupski, who cared for her husband Larry through his prolonged cancer. When the Stupski Foundation relaunched, it did so with a commitment to reduce unnecessary suffering and help patients identify and receive the care that they want, where they want it, before they pass.

We recently awarded $14 million in grants toward those goals over the next three years. If you live in the Bay Area, it’s pretty likely that we are working with the places where you would get your intensive care if you had a serious illness. This first major round of funding focuses on helping health system leaders expand and improve care for patients. I’m sharing where we are today and what we are trying so that even those of you outside the Bay Area can learn a little from our successes and failures and hopefully improve on our approach in your own philanthropy. (When you do, please share what you’re doing with us on Twitter, @StupskiFDN.)

With all the complex issues patients and their families face near the end of a person’s life, why did we start by giving big grants to hospitals and physician groups? These are complex institutions designed for treating acute, specific problems rather than for addressing the broader notion of living well in spite of serious illness. Fortunately, lots of people in hospitals are trying to address that, and if we can help them accelerate change from the inside, then we expect to be able to reach a lot more patients. One group, which we are working with, are doctors and nurses interested in palliative care.

To quote Dr. BJ Miller, palliative care is about comfort and living well at any life stage; it is not exclusively about end of life care or hospice care. People battling cancer, for example, can benefit from having symptoms like pain or nausea mitigated. Palliative care doctors and nurses can help provide that extra layer of support, whether to alleviate symptom burdens or discussing care and treatment options that fit with a patient’s wants and values. These specialists work alongside a patient’s other physicians as part of the broader care team. This is the approach I hinted at earlier. And it works.

We think a good place to start our own grant-making is to increase the availability of palliative care teams. It can happen in inpatient settings (for people spending significant time in the hospital), outpatient settings (co-located with an oncology check-up, for instance), or in a patient’s own home. Over the next three years, the $14 million we have committed should increase palliative care capacity by more than 1,000 patients per year – forever – in San Francisco and Alameda counties.

Our goal to comprehensively improve care in the two counties meant inviting every health system in Alameda and San Francisco Counties to apply for funding. We gave them each grants to plan their programs over the course of five months and met with them monthly to discuss scope, direction, and progress. The back-and-forth helped us see each system’s strengths and idiosyncrasies, identifying places where restrictions on our funding must relax to account for their unique realities. The partnership ultimately led to seven grants supporting Alameda Health System; Chinese Hospital; Kaiser Permanente; Sutter Health; University of California, San Francisco; Washington Hospital; and Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center.

In retrospect, we asked too much of them in a few ways during their planning process, which we’ll remedy if we award another round of implementation grants in the future. As the adage goes, we were only able to move at the speed of trust, and I am grateful to the planning grant teams at each health system for offering honest feedback about how we can make the process better for the future. This is the start of our 10-year spend down; getting the relationships right is an important precursor to collectively being able to identify the best path to impact.

That path to impact is twisty, stretching well beyond the health systems and palliative care worlds. We are also looking at ways to make sure that nobody in our two counties gets left out, excluded from these new services for racial, linguistic, cultural, or geographic reasons. We expect to invest in shared services that will benefit patients regardless of where they get their care, motivated by each planning teams’ enthusiasm for working with the other systems in the area. We are keeping our eyes open for ways to accelerate the move toward value-based care rather than volume-based care, and we are in discussions with local insurers serving the Bay Area.

As delightful as it is to announce the Foundation’s first round of spend down grants, we know we are just at the start of the journey. Palliative care is an important part of the solution, not the only part. Many things are needed to restore lost dignity to a patient diagnosed with a serious illness, and we hope, with our partners, to build a world where they are the norm rather than the exception.

- It is important we acknowledge that the voices mentioned here do not include the voices of physicians of color. At the Stupski Foundation, we are working to understand how we can better center racial equity in all of our work, in partnership with people and communities of color who best understand the challenges patients face in our communities.