On Gatekeeping

This quarter’s first spicy question is from Amira—thank you for giving me the green light to answer your fantastic inquiry:

“What would happen if foundations treated grantees with unbound generosity? I’m talking radical acceptance—funding existing work, funding new ideas, giving unrestricted funding without a firm plan attached, without an end date, and encouraging doers to take risks without abandon. Why is there still so much gatekeeping even after grantees are brought into the fold?”

Before I delve into the wild world of unnecessarily kept gates, a reminder that you can submit a question and/or a rant using this submission form. We will release the next edition of Philanthropy Confidential on Sept. 8, 2025. If I am not able to answer your question publicly, I will try to answer it personally via email.

A foundation employee answering inbound inquiries in a timely manner—what a concept!

Dear Amira,

Thank you for submitting your thoughtful question. I think it’s important for you to know a little bit about the strange person you have entrusted your inquiry to. I intend to answer questions like yours quarterly, with a culminating argument that philanthropy must foster the social conditions leading to its eventual abolishment. I believe that there are a series of nonpartisan policy shifts that can and must transpire to live into this vision.

Tantalizing, eh? That’s the series finale. You’re the pilot episode. Let’s go.

Amira, from a rhetorical level, you—the grantee—know what would happen. If funders practiced radical acceptance and unbound generosity, you’d have more time to focus on the actual work you were founded to do. You could dream well beyond the confounding negotiation you have to make with a foundation and its so-called “strategic plan.” You wouldn’t have to look at your calendar; see that you have a meeting with a program officer; and sigh like a post-divorce Ben Affleck, staring longingly at the Pacific Ocean with a terrible back tattoo, wondering, “How did I get here, what did I become, and why is this world so, so cruel?”

This sounds great, doesn’t it? So, why is it that a majority of foundations simply can’t let go?

Well, for starters, we’re a bit entrapped in a strange philanthropic system whose historical and ideological foundation runs contrary to “unbound generosity”—a corporate-like approach where generosity and so-called “return on investment” (ROI) are in a weird situationship. The lineage of this ideology goes back more than 100 years, entrenched through John D. Rockefeller’s formative perspectives on philanthropy (among other wealthy men). As he writes in his 1909 memoir Random Reminiscences of Men and Events, John D. Rockefeller—of Standard Oil infamy and one of the fathers of American philanthropy—defined progress as:

“… to make investments in such a way as will tend to multiply, to cheapen, and to diffuse as universally as possible the comforts of life … These are the lines of largest and surest return.”

In reading the thoughts of Mr. “Cheap Comforts of Life,” you can already connect the kinds of irritating questions you and countless other grantees have to answer a century later: How will you scale your efforts? What is the per-user cost of your program? Why is it so high? Please disregard that I send my child to private school whose per-user cost is $40,000 a year, which is coincidentally the size of this grant.

Additionally, notice the linguistic disconnect between your vision, Amira, and Rockefeller’s—the “unbound” fullness of generosity versus the linearity of progress. That said, I don’t want to spend more words writing about the incongruity between capitalism’s quantitative ROIs and the undulating, dynamic nature of social change. We know this, and the last thing I want to promote is all of us throwing our hands in the air while offering a resigned, “Urgh, capitalism!” I mean, that’s so philanthropy.

Instead, I want to offer a counterfactual to my colleagues in the field of philanthropy of what happens when we start practicing even a modicum of acceptance—if not much, much more. After all, if we constructed our own origin story, then we can rewrite the narrative as well.

…Why is there still so much gatekeeping even after grantees are brought into the fold?

Amira

Although I use Stupski Foundation as an example, let me emphasize that I do not think we at Stupski are a perfect exemplar for the field—like most foundations, we have made many mistakes, and I anticipate that we will make a few more on the way out. With that said, in this edition of Philanthropy Confidential, I’ll focus on one of the practical things that we got right that’s also a direct answer to the latter part of your question, Amira, on gatekeeping.

One of the best things we ever did was question the amount of gates within our organization and work to shift and/or eliminate them.

If you’re a grantee, you’re probably wondering why 11 months, two Marvel films, and eight tumbleweeds have to pass before you’re able to get a response on the proposal that the funder requested of you. As a general rule, the larger, more layered, and bureaucratic the foundation is, the more internal gates your proposal has to hurdle through—and the more questions you’ll have to answer along the way.

The structural issue that I find at most foundations is the fixation on making the grant (aka the main gate) without a lot of focus on what’s on the other side of the gate—a whole giant pasture of challenges and needs from grantees that our puny grants will not solve. My team has asked grantees what they need “beyond the grant” through surveys and conversations. Grantees have consistently responded: 1) connections to other philanthropic organizations, 2) help with fundraising, and 3) access to speaking platforms so that they can reach the goals that are often dictated by foundations themselves. In other words, grantees want less compliance and more unbound generosity on their terms. These important requests require a lot of people and power on the other side of the gate/grant. For me, our lopsided grantmaking pipeline is the equivalent of spending years choosing a partner only to neglect the relationship on the other side.

The confounding emphasis on that first easy gate—issuing the grant—means that there’s a lot of gatekeepers in the mix holding the gate and making demands. I call this the “Augustus Gloop-ification” of the grantmaking pipeline. Is there a chief program officer in the mix? Well, add two months and a few more questions, why not? Is there an evaluation function on the organizational chart? That’ll be another two months and a couple more outcomes! Does the foundation’s board have issue area subcommittees? You better take out life insurance as your backup grant.

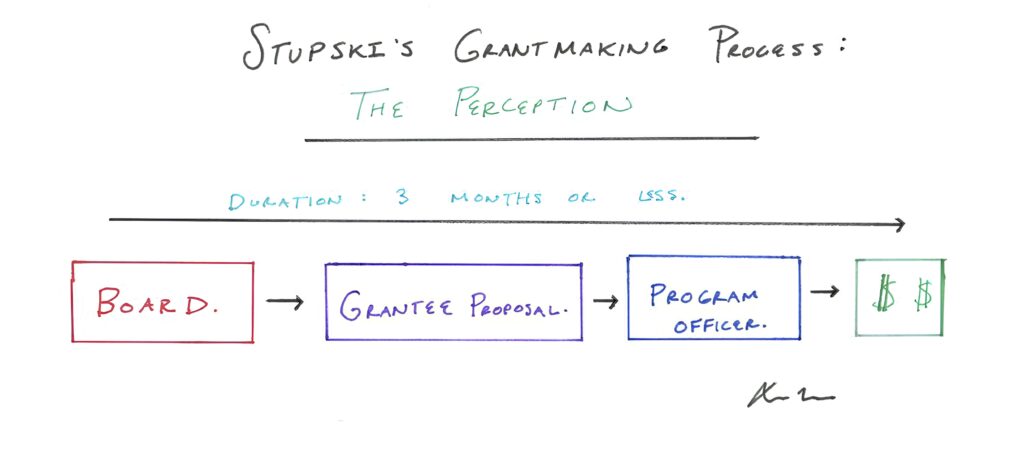

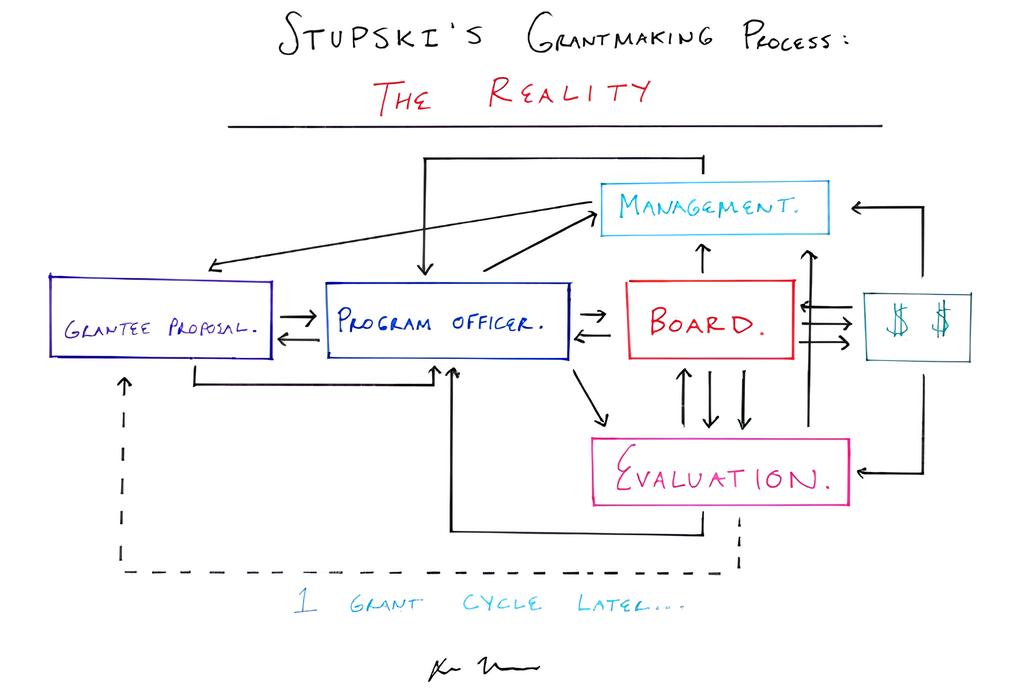

Although each of the aforementioned roles have theoretical utility at a foundation, the problem is when all of these roles bottleneck a grant on the precipice of approval, which is frustrating for all parties involved, especially the grantee. In theory, Stupski’s grantmaking process should have looked like this:

Instead, here’s a personal journey map of what it took to make a proposal a grant when I first started at the foundation:

Under this system, it took over one year to approve some of my first large grants. I used to joke that someone could birth a child and have it terrorize their parents’ sleep schedule for two months in the same time it took to approve a well-vetted grant, which is objectively absurd.

The awkwardness of being a 10-year spend down foundation that takes approximately one year—10% of its existence!—to make a grant forced an uncomfortable yet necessary series of conversations. We asked questions like, where are people best positioned? Do we need certain positions? For the Stupski Foundation, this meant:

- Our management (chief program officers, vice presidents of programs, directors, etc.) should inform strategy, not individual grants. They should greenlight the beginning of grantmaking and not be the ultimate check-off at the end.

- Because board members don’t have the time to get to know every grantee, then instead of approving individual grants, they are best positioned to approve a strategy and an annual budget. Additionally, they can help amplify and support grantees once a grant is made.

- If we trust our grantees to develop their own metrics and outcomes that matter to them, we don’t need a learning and evaluation function at our organization.

Each of the aforementioned role shifts/gate removals took years of internal work, and we are still shifting. Yet, rather than the entire year it used to take us at Stupski to make a grant, we now take less than one month (if not faster) upon receipt of proposal.

Processes, people, and the internal politics look different at each foundation, but the question remains the same: What gates must shift? What gates must go?

Amira, I hope my answer provides insight to your question on gatekeeping in philanthropy. I have a lot more to say about how radical acceptance could make foundations less boring, less privy to funding technical solutions that no one wants (urgh, text-nudging interventions), and much more imaginative. I’ll leave that for another Philanthropy Confidential.

To conclude, let’s return to our frenemy, Rockefeller. What I found most interesting about his biography is the story of Standard Oil’s inception, which Rockefeller distills into the moment he walked into the bank of T.P. Handy, a local banker who was primarily interested in young men’s development. The following conversation ensued:

“How much do you want?” [Handy] said.

“Two thousand dollars.”

“All right, Mr. Rockefeller, you can have it,” he replied. “Just give me your own warehouse receipts; they’re good enough for me.”

As I left that bank, my elation can hardly be imagined. I held up my head—think of it, a bank had trusted me for $2,000 … For long years after the head of this bank was a friend indeed; he loaned me money when I needed it, and I needed it almost all the time, and all the money he had.

It’s the narrative of a young and hungry entrepreneur. It’s the origin story of Standard Oil—one of American history’s industrial behemoths.

It’s unbound generosity.

Amira, you’re on to something.

Thanks for your question. See you again in September,