On Funding Criteria

Over the last few months, I received several questions from grantseekers who have encountered weird funding criteria. The gist of these questions is encompassed by Mark Drexler’s astute submission:

Why are funders limiting grant support to nonprofits over $5 million in operational budgets? This is an artificial way to exclude successful proven business models that are evidence-based.

Mark, thank you for allowing me to respond to your question publicly. Also, shout out to your organization, Wellness Together! For those who are interested in submitting a question, you can do so here. Even if I do not write to you via this column, I will reply to you via email.

After this quarterly edition, I will see you on November 6 for the next edition of Philanthropy Confidential with audio-visual elements—scary!

Dear Mark,

I appreciate your candid question! I’m with you for most of your inquiry. Although I diverge from the idea that we can define “proven business models” in the social sector (I’ll write about that soon!), you raise an excellent point on the infuriating funder standards that you’ve been privy to. I’m excited to dive in.

Mark, the technical definition for what you are experiencing (as I define it) is “Unregulated philanthropic entities who create arbitrary standards that are inconsistent across foundations, resulting in a problematic cacophony of confusing and reductive funding criteria, which is detrimental to social change.”

If you want to stop reading, that’s it. You have much better things to do than listen to another funder describe something in 1,500 words when we could have just used 15.

With that said, as a loquacious and hypocritical funder myself, I see a bigger problem within the stated problem of funder budget limits. That problem is that the artificial, narrow, and “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” standards we as funders subject organizations to actually create more problems—namely that we can’t collectively “solve” anything substantial. The “artificial” cutoffs you are experiencing, Mark, are a perfect example of this. How?

Artificial (and Inconsistent) Cutoffs Force Grantees to Spend More Time in Foundationlandia!

When I see a bullet-point list of grant eligibility requirements, I imagine the well-intentioned conversation that transpired, leading to its creation. Our criteria must be clear and transparent. We shouldn’t waste people’s time. I conjure this back-and-forth because I have had similar exchanges. In those instances, we were aiming for funding criteria that said: “We want to fund small organizations that don’t readily get access to philanthropic funds.”

Let me stave off scuttlebutt by reinforcing that I support this intention wholeheartedly. When a funder puts an organizational budget threshold on a request for proposals (RFP), the generous part of me sees that a foundation is trying to prioritize the people who don’t have equitable access to capital. There is a lot of empirical evidence indicating that it’s difficult to get funding if you’re a small organization without a development team. We should not overlook this.

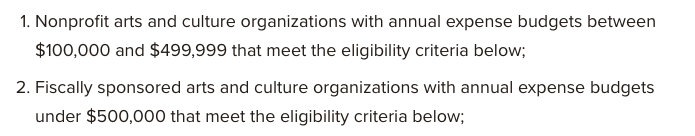

That said, Mark, the word that is really striking in your question is “artificial”—and you’re right. Unlike the federal government, which has rather clear (albeit flawed) income guidelines for tiered income levels, philanthropy doesn’t have unified standards on things like what a “small” organization is. As an example, here’s a screenshot sample of two foundations funding the arts in the same region, similarly aiming to deploy resources to “small” organizations, who are even on the same Common Application …

Your organization can be small for one foundation and big for another. It’s like one of those mirrored funhouses, except none of the fun and all of the terror. And before everyone reverse image searches the above with virtual pitchforks, I’ll put myself in the hotseat as well. As I will say repeatedly, the Stupski Foundation and I do not exemplify the best model for grantmaking. In fact, I helped lead grantmaking where we set the organizational budget size limits. When I think back to how we came up with those thresholds, my best conclusion is a small sample of trends and a whole lot of … vibes. In the words of 21st century philosopher Taylor Alison Swift: “Hi, I’m the problem, it’s me.”

On a serious note, criteria variability translates to nonprofits spending more time prospecting funders and clicking through a bizarre number of links on a foundation website to find eligibility information. Thus, in the attempt to articulate clarity in criteria to save time, funders have created a tapestry of confusing standards that requires prospective grantees to spend less time in the real world and more time in Foundationlandia! Urgh.

In a future edition of Philanthropy Confidential, I’ll map all the subautonomous regions of Foundationlandia!, including the stretches of the Framework Republic and the Leadership Development Gyre. For now, Mark, we begin our Foundationlandia! journey in the Criteria Alps, where few people can get to the top and each mountain climb has its own set of crags and barriers.

How do we make the climb less perilous for grantees? A suggestion that may rankle some folks in my little corner of philanthropy: I think we should get rid of organization budget size thresholds (among other criteria) altogether. Why? Because …

Narrow Funding Criteria Limit Ecosystem Success

Mark, another interesting part of your question is the observation that foundations impose budget limits regardless of an organization’s history and perceived performance. From my vantage point, when I see narrow criteria, I also see a foundation operating in a fear-based manner that limits the imagination of what ecosystems can do.

I don’t just mean budget size. My personal favorite (re: not favorite) form of restrictive criteria is when an education funder tells me that they invest in public school systems change but … don’t invest in public school systems. That’s because schools are too difficult, and funders are looking for a challenge they could do! And then those funders get upset when the disinvested schools fail to meet their expectations. Like, what? Do these people also enjoy punching themselves in the face?

Jokes and possible masochism aside, narrow funding criteria has significant implications. When a foundation severely limits its scope of funding, it avoids the reality that organizations operate in an interdependent and interconnected ecosystem and deserve to be funded collectively. The exclusionary focus bifurcates funding, ignoring that organizations depend on each other to achieve a greater goal. Worst of all, our philanthropic practices foster a crab fighting effect. For example, in education, students depend on a variety of supports—community-based organizations, social safety net systems, schools, advocacy groups, and more. We need the spectrum of organizations, regardless of the organizations’ budget sizes and roles. For funders, I recommend we start leading with what we do fund versus a bunch of constraining bullet points on what we don’t fund—and that we should legitimately be open to an ecosystems funding approach.

I feel the finger wagging already, so as a reminder, as of 2024, $1.5 trillion in funds were locked in philanthropic vehicles as a result of the field’s paltry 6.6% payout. It’s important to keep in mind that philanthropy is one of the few entities in the social services field that can “yes/and” if payouts were higher and funder coordination were more robust.

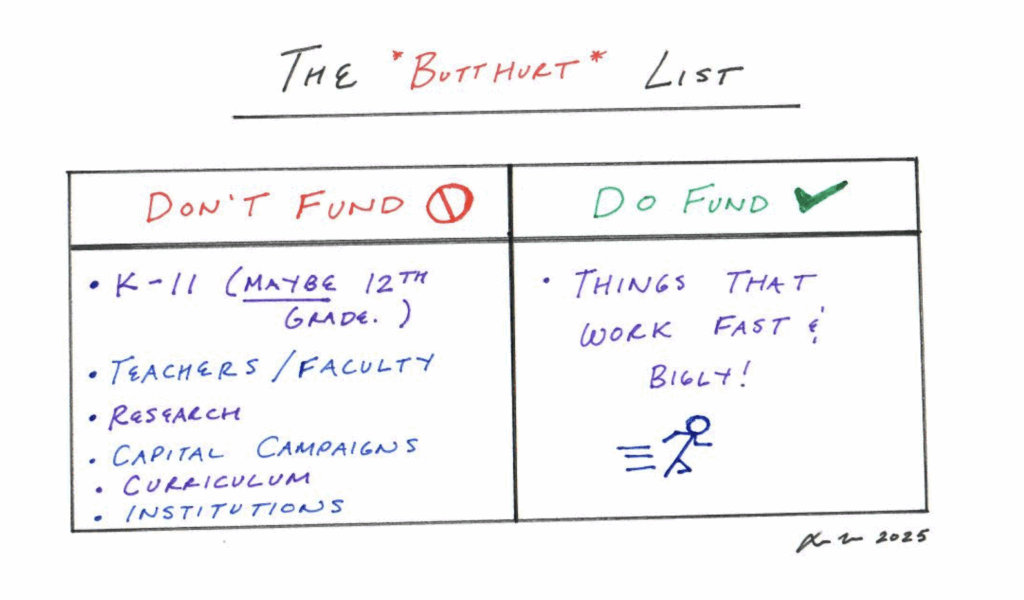

To be fair, most of the time I don’t think the program officer is entirely at fault. Foundation staff members are often the purveyors of what I call the “Butthurt List.” And yes, I am absolutely going to use the word “butthurt” at least five more times in this piece of philanthropic writing—it’s in the Oxford English Dictionary, after all:

butthurt (adjective): overly or unjustifiably offended or resentful

What is the “Butthurt List”? It’s a bunch of things a foundation doesn’t fund because of historical disappointments. In keeping with the “Anti-Hero” confessional, when I began my role as director of postsecondary success, the Stupski Foundation started its spend down trajectory—the last chapter of the institution’s story. Prior to this iteration of Stupski, the foundation existed for nearly 25 years as an entity intended to change educational systems across the country. In the process, Stupski had accumulated a record of initiatives not going as planned.

When I started, those disappointments ended up on my virtual desk in the form of a “Butthurt List,” which looked like this:

I wish I were exaggerating, but I’m not. It’s still unclear to me whether the list was based on actual conversations with our board or conservative conjecture. What I was left with was a very narrow set of interventions that could get past our board. Whether written or culturally instilled, versions of these lists exist at many foundations. By the time a prospective grantee navigates three pages, eight moving graphics, four links, and two PDFs on a foundation’s website to find the open funding opportunity, what they are seeing is an RFP full of criteria distilled from staff conversations on what can get a “yes” from a donor and/or a board.

To the donors and boards who hold the power to shape these lists, a plea from someone who has been the tortured bearer of the “Butthurt List”: Yes, systems change is hard and difficult, but like most things in life, it also requires expansive openness and imagination. Being butthurt is not a way to live and thus shouldn’t be a way to give.

Funders Force Grantees Into a Catch-22

Finally, Mark, the most concerning aspect of the $5 million cutoff (or whatever cutoff a foundation decides) is that it unintentionally perpetuates the “lose-lose” situation that grantees are trapped in. If you don’t meet a foundation’s evaluative standards during the grant period, you may not get funded again. Similarly, if you succeed in fundraising, you become too big and may not get funded again. It’s a classic “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation.

One mentality that perpetuates the aforementioned is philanthropy’s emphasis on Sustainability.™ The reason behind the trademark is that philanthropy has concocted this miracle elixir that by somehow reaching a certain budgetary milestone, it means that the organization can practice ༼ つ ◕_◕ ༽つ SUSTAINABILITY™ ༼ つ ◕_◕ ༽つ

These magical Sustainability™ potions include:

- Using technological automation (that someone needs to pay for) so that the organization can become efficient and financially optimized!

- Providing fee-for-service technical assistance to public systems that, by the way, also need money because they are underfunded too!

- Some weird and vague philanthropic definition of narrative change that will shift the world!

- Developing an investment plan that locks capital in short- and long-term financial vehicles, though that means an organization STILL NEEDS CASH FLOW to operate!

- An assumption that permanent systems change will happen after a two-year grant cycle!

- That fairy MacKenzie Scott! Have you heard of her???

We expect organizations of a certain size to be able to “sustain” themselves, when the reality is that philanthropy as it is currently constructed must fund organizations long term. Of course, there may be legitimate reasons why funders do not continue a relationship, but that should be an exception, not a rule. We cannot budget-exclude and fake sustain our way to change, no matter our magical thinking.

Being butthurt is not a way to live and thus shouldn’t be a way to give.

Mark, I hope I’ve answered your question, which provoked a lot of wonderful reflection. I enjoyed writing to you. Most of all, thank you for affording me the opportunity to directly speak to funders about the idea that we must frame things in a “how can we” approach as opposed to a “can’t fund” mentality.

Narrow interventions create narrow outputs, which fuel the investment-divestment cycle. To quote the Apostle Taylor in her “Letter to the Swifties 5:8”: “Bandaids don’t fix bullet holes … if you live like that, you live with ghosts.” In other (less deficit-based) words, the ecosystems that are working hard for social change deserve more imagination and expansiveness than that. It begins with funder criteria.

Thank you so much for your submission (feel free to submit another one), and see you all again in November!